I think about the repertoire and music history as a kind of shared, common subconsciousness. Interview with Simon Steen-Andersen

I wanted to ask about your newest project – Don Giovanni’s Inferno. This is the third and perhaps the most ambitious of your works based around canonical operas. You covered Wagner and The Ring Cycle in The Loop of the Nibelung, then Il Ritorno di Ulisse in Patria by Monteverdi became the framework of your piece THE RETURN, commissioned by the Venice Biennale. How is Don Giovanni’s Inferno different from those two?

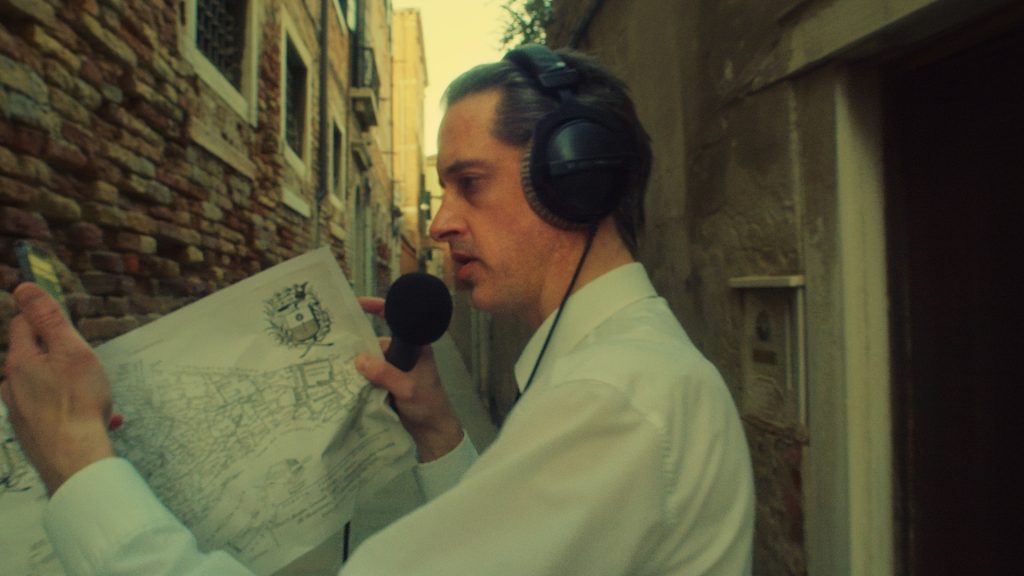

I think it’s a „natural” third step in the same direction. The Loop of the Nibelung is still a Run Time Error – it has its starting point in a location, a very special one [Bayreuther Festspielhaus]. But it expands towards exploring not only the space and the objects I found inside the opera house, but also the history, the music, the associations, the ghosts of the place. And the house itself becomes the scenography for the Wagner-fragments. It all comes from the location. In THE RETURN I’m still working with the exploratory logic of Run Time Error, but I’m moving away from the physical location as the starting point, and instead using the score, in this case Il Ritorno di Ulisse in Patria by Monteverdi. But I ask myself the same questions and do the same kind of exploration – what are the interesting elements in this score, what are its hidden corners, what is the history surrounding it and what is the most interesting route through the „found and selected objects” or „locations” of the score. The „organised sounding objects”, which could be said to be the main thing in Run Time Error, is barely there anymore and only where it can serve or represent the narrative. I myself am still partly present as a leftover, but my presence is reduced from performer to the role of a misplaced, unexplained documentarist. Because the opera was premiered in Venice and the story calls for a maritime setting, the location does play an essential role, but as a part of the history of the score. So in this sense, it did feel like a next step, as the weight was shifted from the location to the score as the object of exploration.

Don Giovanni’s Inferno goes even further in this direction, it leaves Run Time Error as a starting point, but it still uses or transforms its main idea in different ways. Here the opera repertoire becomes the explored location, so to speak „opera as a found object”, objet trouvé, if you will. At the same time, I also explore and use the physical location extensively – the opera house, that once again becomes its own scenography. But even if the subject of the exploration changes, the working method is not so different from when I was doing Run Time Error ten years ago. And there are probably more things connecting the three works, than separating them.

In The Loop of Nibelung, there is also a parallel, documentary-style narration. I used old recordings of the Norwegian singer [Kirsten Flagstad], where she sang and spoke about Wagner. Interwoven narratives, one of which is a documentary of sorts is also present in THE RETURN, where I’m talking to experts, seemingly trying to solve the issue of the location where Il Ritorno di Ulisse in Patria was premiered. In Don Giovanni’s Inferno this idea is turned around a little – it’s not about the documentary vs. the exploration of the physical space or the score, it’s a balance between two fictional perspectives. One is the opera-plot, where we follow the character that Mozart left us with. The other one is still fictional, but based more in reality, as it imagines the subconscious of the singer who sang the last scene of Don Giovanni, then jumped into the trap door and hit his head on the way down. He lies unconscious in the sub-stage and has a nightmare of sorts, where all the characters he’s played and played up against in his career mixes with memories of dictatorial conductors and stage directors and of course the impressions of the back-and substage areas of the opera house. Those two perspectives are intertwined, so we are not sure if we are following the plot of a fictional opera character or the coma-dream of the singer.

In one of our previous conversations, you told me that The Loop of the Nibelung was a transitional piece for you, in the sense that it was a meeting point for previously separate paths of your work. Could you tell me more about that?

For a long time, I felt like I was following three different directions. I was interested in all of them, so I tried to distribute my time equally among them. One direction is the idea of staging more or less isolated from composition. I investigated it for the first time in Inszenierte Nacht (2013) and latest in Music in the Belly (2022), which is a new staging and expansion of a Stockhausen piece. Secondly, there is of course also the direction of my „original” works, where the focus is more on the composition — even if it’s mostly not only concerned with sound. The third direction is the Run Time Error series, very concerned with location and everyday objects. Slowly, I realized that they are in fact not three different directions or interests, or at least there was one very important thing connecting all of them – the idea of working with changing the perspective on something familiar. I do this in my stagings, but also in my composed works — for example, in Black Box Music I would repeat things again and again, with the purpose of establishing a logic that I could break at some point, i.e. first making it familiar in order to then turn it upside down. In Run Time Error, I would take everyday objects with a specific function and use them in a different way – specifically to make music and thus change our perspective on them. The realization that it’s in fact the same common interest came quite late, strangely enough.

I know it’s cruel to ask about the things you said almost ten years ago, but preparing for our talk today, I read an interview with you in Seismograf, titled I am a composer. Nowadays, you are referred to as a composer and stage director. I wonder if you still see staging and directing as the extensions of the role of the composer, or did something change for you in this matter?

I think nothing changed, except realizing that people aren’t too eager to let a composer stage direct. It took a lot of time to convince people to trust me; to let me do it in my own way. I’m collecting this title in order to avoid having to persuade people each time. I believe that it’s mostly an expansion of my role as a composer, and that I have reached the point where those two roles cannot really be separated. On one hand, I would say that in Don Giovanni’s Inferno, it doesn’t really make sense to call me a composer as I have literally not composed a single note. A lot of the time, I am not even chopping things up the way I did in TRIO – breaking them down into particles or building blocks. I am taking ready-mades – characters, sentences, etc. – sometimes twisting them or putting them upside down and then arranging them into a landscape that I plan a guided tour through. On the other hand, nothing changed in the way I work or in the way I think. The role of the director is merged with my role as a composer, and the choices that I’m making and the focus that I have (e.g. on timing) are a product of my expanded compositional practice.

About 20 years ago, I had an idea for a music theatre project, specifically Buenos Aires, where the elements and roles of composition, stage, text, narrative and direction would be fully integrated. I pitched it several times, but people didn’t want to let me direct it. They were very interested in the concept, but only with somebody else directing it. For me that made no sense, as I saw it as one, so I decided that I would wait, or not do it at all. It took ten years [Buenos Aires had its premiere in 2014], and during that time I was strictly working on music, but slowly expanding it to encompass all elements present at a live concert, while being careful that it in fact didn’t become theatre. For me, it was a gradual and natural expansion of the music. When I started to pursue staging, I was just a last little step away from music theatre, so there was no big change, except the mental box. Of course, it’s different to work with singers than it’s to work with instrumentalists, especially if their actions are not strictly musically motivated, but the difference didn’t feel that big to me. With musicians, you are already concerned with the attitude, the movements and the physicality that always plays a role, and you find ways to go with it and convey it in music. Starting from this point my later work with actors also felt like a small, natural next step. I always had an opinion and preference concerning all aspects of the act; it felt natural because I also composed or arranged and conceived it, so all the actions were coming from music or were related to music in one way or another. I think that my being a directing composer may, in the best case, also bring aspects to the piece that wouldn’t have come about if somebody else were to direct it, simply because I’m coming from a different angle of approach.

Also, in the whole „expert” discussion it really helped me to see and explain what I did as an expansion of the musical or sounding material, rather than seeing the visuals or staging or whatever as additional layers. You go into a new creative area, and you are afraid, because other people have studied this field for ten years, just like you studied yours. If you look at what others are doing, and you try to follow them, because you are scared of making mistakes, at that moment, you lose something. You do in fact become an amateur, whereas if you don’t change your personality and way of working, when you change or expand your media, I believe you can stay the expert. You are composing with a different medium or out of different aspects, but you are just expanding your working material or juxtaposing your way of working. This image has also proved helpful when I try to explain my role as a director to producers. I also try to make my students conscious about this idea of not changing your personality when you change the media. Of course, you still need to get experience with that new media, but there is only one way to get that – by doing it, and sometimes you can turn a fresh or even naive approach into something positive, into an advantage.

I wonder how staging Stockhausen is different from staging your own music?

Music in the Belly is special in this sense, because most people don’t know it, so it doesn’t belong to the cultural memory. It’s not the same as working with something that people are familiar with and transforming or juxtaposing it. It’s more similar to the situation of traditional staging – most theatre directors are neither working with a text of their own. In this case, I am working just like most other theatre directors, I guess – searching for the interesting aspects, extracting or emphasizing certain things, trying to find new perspectives, making an interpretation, maybe cutting some of the material out or swapping things around, perhaps even integrating foreign elements or texts, etc. In many ways, it’s more of a traditional staging, but it’s of course very much informed by my work and background with sound. In fact, the most important part of this staging, in my opinion, takes place inside the music, which doesn’t happen often in music theatre and opera.

You mentioned changing the perspective, extracting or emphasizing certain aspects of the piece, which affects the whole dynamic of the piece. I feel like the category of dramaturgy is always strongly present in your music.

Before I started thinking about it as a dramaturgy, I just thought of it as a form. I was trying to understand what creates tension and dynamic; what makes it worth talking about form as something other than just the order of things. In the music academy, people were always throwing around those terms, and it made me think – what does form even mean? My personal conclusion was that it doesn’t mean anything, unless you find a way to make it a parameter that has almost an abstract quality in itself. That became my way of understanding form. One very simple example of this is to have elements that really come and go throughout the whole piece, but at a different rate or at a different intensity, so that it creates a dynamic process present in the whole piece. At some point, I realized that many of the things I was doing and searching for could be better thought of in terms of dramaturgy or film editing. I was already doing very quick cuts between different, very identifiable materials. It was a bit like cutting between scenes in a movie. You don’t necessarily connect those two scenes chronologically; you don’t think that the amount of time that we spend in the other scene must have passed in the first one. Rather, you have this feeling that they exist simultaneously, and you start connecting the fragments in your head. This is a phenomenon also known in music, but on a much smaller scale. We can have individual notes spread out over registers, and during listening, we start to connect all the notes in one register, and all the notes in the other, almost as if there were continuous lines. It’s called pseudo-polyphony in English, and it’s basically a Bach violin partita with singular notes, where we have a clear feeling there is a melody and there is a baseline. We don’t think of it as separated points or dots; we think of it as lines.

In the past, you explored the complex relationship between the visual and sonic layers in your pieces, often using the distortion of audiovisual elements. Nowadays, your music seems to lean more into visuals supporting the audio, and the narration is more linear and clearer. Would you agree, and if yes, where did this change come from?

I think in some of my projects, the role of the music has been diminished a bit. In a certain way it was given more of a supporting role, but it really depends on what part of a piece one is looking at. It’s kind of a self-critique, because I don’t like using music as an effect, and there is a danger of the sound becoming one, if it just comes to support a moment of a narrative. But I’ll do it when I think it’s worth the sacrifice. For example, there are many effects in TRANSIT – sounds that are there mainly to support a certain mood or to evoke a certain genre as a reference. That is something that I would have avoided in the past. You could say that now I am thinking more about what I want to achieve and less about how to get there. But in TRANSIT there are other elements; for example, the voice of the tuba player, reverbed as if he was inside a giant tuba, but the performer also plays the instrument, and little lights and props move around inside the tuba, which is seen as the video endoscope moves through the instrument. I think that’s a good example of instrument, music, narrative, text, sound design and staging being completely intertwined; it’s so self-referential and interconnected that you can’t really separate it. I wouldn’t say it’s the visuals support the sound in this situation, but everything is somehow coming from and pointing back to music. Regarding the narration becoming more linear and clear – yes! You could say that I chose to reduce one kind of complexity to make space for another one. The complexity of meaning and form, if you will. One thing that guided me was the realization that, for me, the complexity or ambiguity coming from various kinds of distortion or blurring of elements was less interesting than the ambiguity deriving from combinations of opposing or incongruent elements. And I found that the clearer the opposing elements, the stronger the experience of ambiguity. It introduces a dynamic experience and a kind of complexity, where the interpretation becomes unstable and unsettled, where it becomes dialectic.

I feel like this is a standard question for any composer whose work is heavily based on references, but I can’t help but wonder – how important is the sound itself for you?

Let’s make it relative – I think it’s very important, but I used to find it even more relevant in the past. Or maybe I don’t find it less relevant, but I simply already did those works, where I really took care of it, and now I’m trying something else. I had some experiences where I thought that the concept was so interesting to me, that even if the music was playing a role only to provide us with this experience of the concept, I would do it. Of course, I’ll still do everything I can to make a sound special, even if it has more of a function than its own right. I’m very interested in the sensory experience and the form as well, but I also enjoy a good concept. There are extreme cases of concept art, where you have to admit that the realization of an idea wouldn’t add to the experience of depicting it in your head. I love that, but for me it’s not enough – I want the strong idea that you can appreciate in itself, but merged or realized with something sensory and dramatic, that you couldn’t predict from the idea and that adds something essential to the idea and a strong experience in the now.

Seeing your works like is always a deeply immersive experience. I think the complexity of your work is one of the reasons why it is so interesting – the audience has to constantly question things they see and hear, and process all the different material that you are offering. When you compose, do you think about the level of understanding among the audience? Is there a concern about whether they are going to pick up on those different references?

I think a lot about what can be communicated. At the same time, I don’t expect everyone to pick up on every reference. In the case of The Loop of the Nibelung or Don Giovanni’s Inferno, if you know opera, you will get the thousand references you wouldn’t recognize otherwise, but I think it still works as a reference more universally to tonal music, or a certain genre. It’s a bit weird, because I love all these references, but I also believe that those pieces can absolutely be experienced and have value without them. In fact, if the experience becomes a quiz, I think that will be a bigger problem for the experience. Even if I know all the operatic references, a part of me is still an opera-outsider who has no idea, or maybe even no real interest in opera, so I can still empathize with that perspective. I have always found this famous quote from Mozart a bit arrogant – that he was composing both for the experts and the amateurs. But in a way that is what I am aiming for. I don’t evaluate who is the better recipient; I just think about this multitude of layers, elements, and interpretations. I’m interested in all those different perspectives and angles of entry; I don’t think the references per se are more interesting than the sonic, sensory, or even energetic, bodily experiences. I always try to ensure that there is communication, even if it’s happening on different levels. If it’s perceived in a different direction than I hoped for, it’s still communication – it starts an interpretation, creates meaning and dynamics between different meanings, and I think that is important for me.

We talked about the narrative complexity and the amount of references, and meanings in your work, but there is also the complexity in a technological sense – I am thinking about Run Time Error, Walk the Walk, or TRANSIT. All of those pieces require equipment, precise timing, and extensive technical supervision. How do you view the relationship between those two kinds of complexity? Is the technology behind the performance a tool that you use to get your message across, or a separate interest of yours?

I would say it’s a tool. I am not so fascinated with technology itself. Maybe some analog technology? But it is very difficult to separate the interest in the analogue from nostalgic qualities, something that has more to do with its ”aura” than with the technology itself. In combining the music with the visuals, I am always looking for connections, a certain kind of integration. My experience with Don Giovanni’s Inferno is very much the experience of suddenly having a whole different scale of available technology. It is not high-tech; it is mostly stage mechanics. Well, if we also call mechanics technology, then I guess I am quite fascinated by that specifically, but again, I don’t think it is an interest in the technology itself; rather, it is almost a performative interest. For example, a revolving stage, I like both the kinetics of the people moving on it and the entire construction itself, the sound of it. The first time I went and asked about the revolving stage, I heard, ”You have to know it’s very noisy; only if the orchestra is playing really loud, we don’t hear it.” To which I said, ”Perfect, let’s amplify it.”

When I think about the various references in your work, the term ”play with collective memory” comes to mind. But there is also individual memory – in TRANSIT, The History of My Instrument, The Loop of the Nibelung? How do you see the relationship between those two kinds of memory?

Such an interesting question. I haven’t necessarily thought about it in that way. Yes, the collective memory is something I think about a lot. When a work is based on various references and histories, you automatically tap into the collective perspective and collective notion of things. In TRANSIT, it’s very clear that we also have the biographical element, but it’s rather the exception. I really like it, though; it’s a space that allows me to pursue more dreamlike or surrealistic qualities from a subjective perspective. I have always been interested in things changing meaning and value, showing multiple sides of the same object, and transforming perspectives, so memories and dreams seem like plausible spaces for those surrealistic connections. I find myself more and more looking for ways to get in there.

Just like in Don Giovanni’s Inferno, where we have a dual perspective – one being the opera plot and the other happening in the singer’s head.

Exactly.

And in The Loop of the Nibelung, on one hand, you have this linear narration, very quick-paced, interwoven with the documentary about Kirsten Flagstad. Of course, being the famous Wagnerian soprano, she is also a part of the collective memory, but it feels very personal – we hear her voice as she sings and tells her story.

Yes, I think in a way she becomes a character in the story. And a similar thing happens, for example, in TRIO, where some figures of the conductors come back, again and again. I like this idea of having characters in parallel narratives to the main one. The common thing about all these ideas is that they all start with the archive. It is a part of the research, finding this aura around the main topic, which could be the opera house. We find all these characters, elements, ghosts, and music, and then if there is something interesting, we follow it, and it becomes a character – connected to the main narrative, but sort of in its own right. Sometimes I have a feeling that it is not my idea – it is just something I found and just fitted it together. That may be quite a fitting description of a lot of projects that I do now, where I am starting with this extensive research phase. I am just gathering these puzzle pieces, and then I am trying to clean them up, and see what could fit together. For example, while working on Don Giovanni’s Inferno, I read the Don Giovanni libretto probably 50 times, trying to locate and extract all the little interesting details, and look for all those sentences that could be taken out of context and mean something else. Often, my best ideas come up in the research, in exchange with the material.

We talked about those different kinds of memory and the process of arranging and rearranging, but there is also a question of timelessness or continuity of musical message. For example, in Don Giovanni’s Inferno, where you pick up the plot in place where Mozart left us nearly 230 years ago. My last question is – is that perspective important for your work, or do you simply view the music of the past as a rich source of references?

I think it’s a bit of both. One way of creating depth and self-reflection in music is to expand it into its past. It creates a dynamic and multidimensional situation, and it doesn’t necessarily have to be a comment on the current musical situation. I expand into the history as an unfolding of one dimension of the found object, just as I try to unfold other dimensions, too. I don’t think of it as a continuation of a musical message, but I do have a feeling of timelessness in the sense of memory or the subconsciousness. I think about the repertoire and music history all the way up till now as a kind of shared, common subconsciousness, where everything exists at the same time.

In collaboration with Warsaw Autumn festival, where TRIO along other works by Simon Steen-Andersen will be performed on its final concert.