Hope in the Sound. A conversation with Annea Lockwood

Piotr Tkacz: A trip to Berlin for The Sound of Distance was my first trip abroad since February 2020. I live in Poznań, which is less than 300km, so it doesn’t seem like such a long journey, but on the day I was travelling there were strong winds. Waiting at the station, I noticed that a lot of trains were delayed, up to 3 hours, so I was quite happy that ours left only a few minutes after schedule. I thought that maybe there was a chance we could arrive on time and those 15 minutes I had to get from Hauptbahnhof to Haus der Kulturen der Welt to be on time for a concert would be enough. I soon realized the train was lagging, the wind seemed to be getting stronger, finally it was announced that on that day the train terminated on the Polish side of the border and there would be a bus to take us to Berlin. Of course I thought that I should have taken an earlier train, so I’d already be at HKW. It turned out not to be the case – at the final station there were already a lot of people waiting for the buses, among them an outspoken woman who was very calm and even witty – especially for a person who had been waiting there for 6 hours. Every hour someone from the staff was calming them that the bus was on its way. The story that was told: the German crew was gone, as Deutsche Bahn had decided that it wouldn’t operate in such severe conditions. What a comfortable jumping board to juggle with some well-known, old-fashioned but always handy stereotypes and animosities. I was trying to distance myself with headphones, but on the other hand didn’t want to miss any announcements as the situation was still unclear. Finally the buses came and we arrived in Berlin just as the last event of the festival was ending. But probably this whole situation pushed me harder to ponder upon distance and its implications than any artistic undertaking would – such a prosaic thing as a border, even in the EU, is still a thing that can be palpable… Since then it has only become more poignant as people are dying on Polish-Belarusian border for weeks now. And weather, which is also something allegedly obvious, but more and more we realize it’s out of our control. The next day it was still windy and rainy in Berlin, so I could enjoy Dusk finally on the third day – and what a joy it was that there was sun to accompany it (or vice versa)! If I’d try to squeeze a question out of all this, it’d be: what are your feelings/thoughts/intuitions about the relationship of sound and distance? Have they changed during the last 20 months?

Annea Lockwood: I am sitting in my kitchen stretching my ears and mind to encompass ‘distance’ and finding that the usual ambient mid-range hum of local machinery and traffic makes distance hearing beyond the range of that hum impossible, even though it is relatively low-level. That hum acts like a border wall enclosing my sound world. On the other hand I was recently standing in the garden of a farm in the hill country of Styr, Austria where both my eyes and my ears stretched out for what felt like a great distance – a very quiet place, visually and sonically. Local sounds were aperiodic, not continuous, and felt sharply defined. I felt such a sense of balance in that environment, coming from both the calm of the undulating view and the soundscape. The local hum I referred to above did not ease during the past twenty months but being able to be in my backyard, surrounded by trees and sky and quiet neighbours – that spaciousness – always eased the internal tensions of Covid-time. The sounds of that space close to me were particularly vivid, I think because they reminded me of living things continuing on beyond the constrictions of the pandemic.

PT: What I find fascinating is that sound is able to cover distance, even some physical obstacles, but also create distance in such forceful, encompassing and different ways.

In Dusk you brought together sounds from very varied environments, was it because of their acoustic qualities only or was their origin also important? Should the listener know about that or is it better to listen blindly?

AL: Dusk was published on a CD titled Ground of Being by the Recital label in ’07 and in my liner notes I acknowledge the main sound sources:

Recordings of seafloor ‘black-smoker’ hydrothermal vents made by Dr. Timothy Crone and colleagues in the Main Endeavor Field on the Juan de Fuca Ridge off the coast of Washington State, USA. The bat recordings are from the library of Avisoft Acoustics, Berlin. The tam tam was performed by the superb percussionist William Winant and recorded by Tom Hamilton for this piece. Dusk also incorporates sound from my “Glass Concert”. But I don’t feel that knowing this really affects how one listens or how the piece communicates.

Acknowledging the sources is always important to me because they often come, with generosity, as a gift to me. People are particularly fascinated by the vent sounds I have found, but unlike the installation work with Bob Bielecki, “Wild Energy”, where the origins of the sounds we use are the core message at the heart of that work, with Dusk my choice of sounds was because these sounds are evocative of that time of day to me, my favorite time.

The seed of the piece was Willie’s beautiful extended resonances on the tam tam, recorded at the end of the recording session for Jitterbug. He was stroking the tam with a superball mallet and I asked him to continue so that it could be recorded. That last sound’s fade-out was entirely acoustic, created by his super-fine control, not electronic. It sounded crepuscular. Once I had those sounds to work with I searched out compatible sounds which could create a special acoustic and expressive space together, the title came to me and the piece grew quite fast.

It seems to say something to people whether they know the origins of the sounds or not.

PT: Listening to Dusk (and other outdoors presentations) during the festival I was reminded of a concert that Charlemagne Palestine played on a carillon next to HKW a few years ago which was magical because the sounds seemed to encompass the surroundings but not in a forceful way – more like blending with it, embracing the space. What was also unusual was that the performer or even the instrument weren’t visible. Often I get a sense that people still need to see to believe and don’t really trust their ears (maybe rightly so?).

At least since musique concrete a relationship between seen and heard has to be taken into consideration. How do you approach this, whether working with field recordings or with other sounds?

AL: Much of the time I like to focus entirely on sound in my works, feeling that the eyes co-opt the ears far too fast, often, so that the sound turns into an audio track for the visual. So I prioritise the ears. Visual elements are however integral to the three Sound Maps, which are actually installations. Each comes with a large physical map of the river (printed on canvas), with the recorded sites indicated on the map, together with the time of day and date of the recording, and the time in the run of the piece at which a particular site enters. Listeners can orient themselves in that way, which is much appreciated by visitors who know the river.

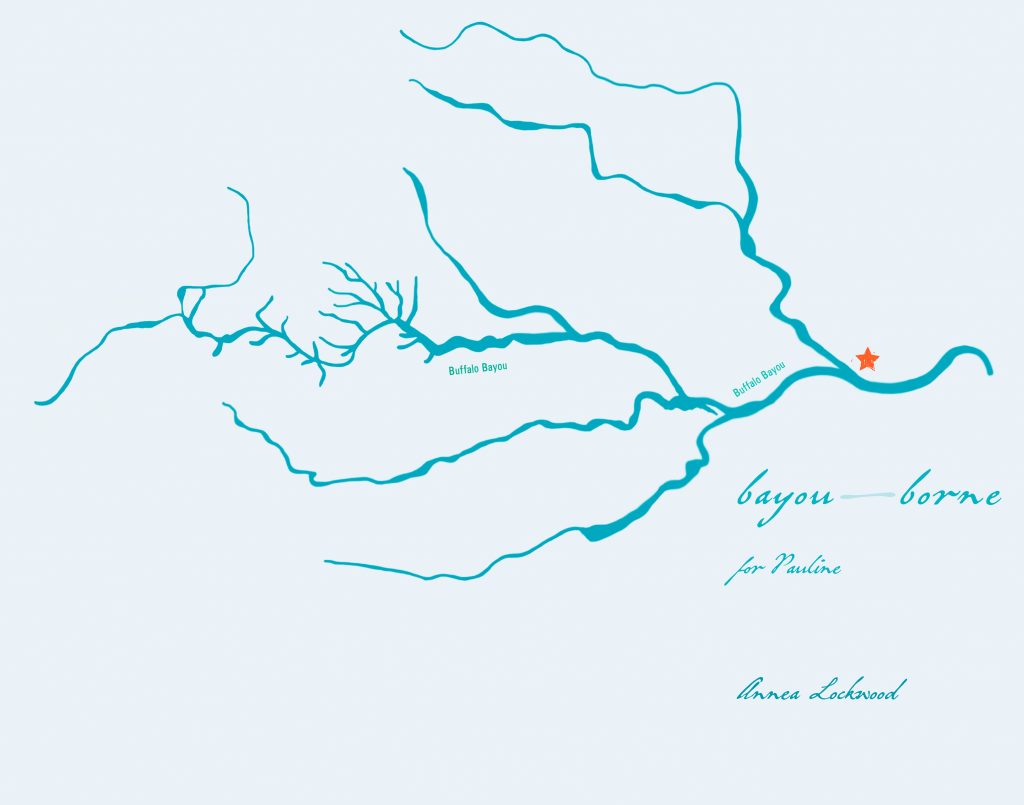

And in Thousand Year Dreaming images of the animals in the Lascaux Cave paintings are projected behind the players and are very much integral to the piece, which was partly inspired by them. bayou-borne, for Pauline (which you may have heard at HKW) is a graphic score based on a map of the bayous in Houston, Texas. Since I ask the players to move through and around the space while they are 'reading’ their river as a guide, they need to be able to see the score easily without the need for music stands. Projection solves this and the visual becomes part of the piece.

On the other hand, although photographs of rocks are the actual scores, (read as graphic scores), in Jitterbug I specifically tell the players not to project the images to the audience, to prevent listeners from becoming entangled in trying to relate what they are hearing to the image’s details – something which is futile and distracting. Listeners often come up after a performance, to look at the images (on players’ iPads often), and of course that’s fine.

The “Glass Concert” was very visual. I don’t recall ever making a piece in which the players were continuously invisible though. Good for Charlemagne!

So it varies, across my work.

PT: Yes, bayou-borne, for Pauline was one of the highlights of the festival for me! The only thing I didn’t like was that it was so short (I’m not sure it was even 20 minutes), of course, you can only look at a river for a short moment but in general I associate it with a longer journey, so it’d be good to spend more time in this environment. Was there any particular reason that you decided that this piece will be dedicated to Pauline Oliveros? And I can’t resist not asking: why rivers (not only in this piece but in your works at large)?

AL: I’m delighted that you liked bayou-borne, for Pauline so much. From the audio I’ve received and a short video clip I know that was a most beautiful realisation of the piece and feel lucky it was in the hands and mouths of those particular musicians – all of it assembled by crys cole (she is so impressive and a beautiful musician herself). It is dedicated to Pauline Oliveros, who was an old and cherished friend, because the piece was one of 85 pieces requested initially for a celebration of Pauline’s 85th birthday at McGill University in Montreal and of her life. Sadly it transformed into a Memorial: “Still Listening: New Works in Honor of Pauline Oliveros” (2017) when she died not long before the planned celebration. I had already written my contribution some months before her death, and bayou-borne… refers to her in several key aspects: as she was born and grew up in Houston (where the 6 bayous converge). I thought she probably knew these rivers intimately, having fallen in and swum in them as a child. She was a brilliant improviser and of course the piece is a guided improvisation, so my thought had been that she would have fun working with this particular material. Then I discovered that in fact an underground reservoir located right on Buffalo Bayou had been emptied and was being used for various public gatherings, so it seemed made for Pauline to resonate. I ask the players to let their sound darken and become intense when they are all absorbed into Buffalo Bayou. These are usually sluggish, calm rivers but their character changed powerfully when Hurricane Harvey hit in 2017 and they became fierce conduits for floodwaters, devastating the Houston area and causing many deaths. The darkening and increased turbulence I ask for acknowledges both that disaster and the instability of rivers and streams – very obvious now that climate warming is upon us. Why rivers? Since my childhood I have been fascinated by them, their sound world, their power, how and why we humans revere them. As for many people and cultures worldwide to me they are alive, living beings, and the sounds created by moving water remain some of the most complex sounds I know. What river do you love?

PT: That is a tough question, I’ve been thinking about it in four different cities, two of them, Cracow and Warsaw, at the same river, Vistula, and two of them with very different relations to its rivers. I’ve just come back from Wrocław, which always impresses me with how well-integrated it is with its river Odra – for example, there are so many bridges and boulevards. There is a sense that the city is not only by the river but that it lives with the river. Then of course is the other side of this integration, kind of questioning it, namely floods – in 1997 Wrocław was heavily destroyed with what was called „the flood of the millenium”. In my city, Poznań, the situation is different and I remember growing up here and thinking that the city turns its back to the river Warta. Once in a while there maybe was an open-air concert but that was more of an exception than the rule. When thinking about a place to go for a walk or biking river was never an option. In the last few years it’s getting better, there is a „water-tramway”, proper biking routes, during high season there are places with food and drinks, even a kind of club – I really enjoy DJing there because the surroundings play their part, it doesn’t make sense to blast hardcore techno at 5pm in full sun but the vibe is changing gradually as the sun is setting down. It’d be the easiest answer to say that I love the river in my hometown, but it’d be an overstatement, it’s more like I’m still getting used to it. I also started going through various rivers encountered during travels in the past and I recall being amazed how vast Danube is in Vienna and then Huangpu in Shanghai, but they felt more like lakes than rivers in a way. Also, being a tourist I didn’t develop any significant relationship with any of them. In the meantime I’ve attended a recital of Schubert’s „Winterreise” and began to read Ian Bostridge’s book about it – thanks to that I started to realize how significant rivers and streams are in this work. That again reminded me how widely they can be used as metaphors and to what startling effects. And then again, trying to find an answer to your question, I even began to suspect that maybe I’m more of a „sea person” than a „river person” – if such a distinction even makes sense. But please don’t ask me about my favorite sea.

AL: Your comment that Wrocław lives with the Odra river is lovely and something I found all along the Danube too – some towns and cities cherish their waterways, when they don’t bury them. That is largely true of New York also, I think. On the other hand, in Philadelphia, in the city, a roaring wall of industry, trains, noise and hardened banks made sensing the river hard, one was defending against the noise so much. However, in my little river town of Peekskill there is a popular walking trail and park on the Hudson which is part of a walking/biking trail extending north from NYC up the Hudson into the Catskills, or thereabouts, which is gradually being created – such a lovely alternative to development. People care. In giving talks I often refer to the growing practice of protecting rivers by giving them the legal status of personhood, initiated by the Te Awa Tupua tribe in collaboration with the New Zealand government in 2017, which protects the Whanganui River along its entire length and gives it all the rights of a person. Such a brilliant approach is now being copied elsewhere.

PT: How was Tectonics? So far I’ve only managed to follow this year’s Glasgow edition because it was online.

AL: Tectonics in Athens was excellent – stimulating and very well-organised and supported. I loved it, my work, A Sound Map of the Danube, was beautifully presented, I managed to hang out with friends I rarely see, even see something of Athens – a great time.

PT: Do you ever think of changing, like expanding or removing, anything when presenting a work like this in a new situation?

AL: That’s an interesting question but no; the specific acoustic of each new presenting organisation’s space affects speaker placement, of course, but not the shaping of the sounds themselves; these are finished works, to me, and I rarely go back into them, except occasionally when making a stereo mix for CD release, in the case of the installations.

PT: I was asking because of course those portrayed rivers have changed in the meantime and also nowadays it’d be possible to conceive such a map with crowd-sourcing tools like Radio Aporee. What do you think about such a participative approach?

AL: Such a crowd sourced work would of course be fine but it is not something I myself am drawn to. I deeply love the experience of listening closely to a site in which I am physically present, learning its soundscape, selecting where to record and how and then working that recording into the weave of the whole composition.

PT: Do you think in terms of, let’s say, truthfulness when working with field recordings? I mean something along the lines of representing the place faithfully.

AL: “Truthfulness” and “representing” and “faithfully” are concerns arising from a different stand point than that which draws me to record out in the field. Sometimes conveying a sense of place, or rather, a glimpse of that sense is a goal, as with my recordings in the Danube Delta, through which I hoped to transmit that immense quiet, and the peacefulness it brought us, without quite knowing how I could do that – hoping that the aspiration would translate into instinctual choices of when to press ‘record’.

But more often I am trying to record how a river’s energy flow translates into its sounds. Those sounds are subtly transformed by the precise mic and recording equipment I’m using, such as the choice to record at a sample rate of 96k Hz or 48k. Other things such as the angle and placement of the mic, (I usually use a stereo mic, rarely an omnidirectional mic, and a hydrophone), color the recording. The sounds present at a site change subtly throughout the day, with variations in flow, with wind or its absence, with the season, with temperature changes – so many variables at play. It’s all mobile, full of transience, a flow, so trying to pin a site’s nature down, in order to “faithfully represent” it, seems impossible and a diminishment of its fullness and richness. On my maps I identify the time of day and the date on which a particular recording was made, as well as the place, with the intention of conveying just how narrowly specific that recording is – a sliver of the sound the river created there, then. They are not representations of the Hudson, the Housatonic and the Danube.

My aim, the thing which drives me to work with water as I do in the sound maps, is to draw a listener inside the sounds, into the river, so that your whole body is open to the river and, the crucial thing – one with it. Accordingly, I use very little processing – wanting you to receive these sounds as directly and physically as possible, even through this virtual medium.

On the other hand, sometimes, as with Bouyant (an electroacoustic piece from 2013), I build a piece around a field recording made simply because a particular environmental sound field is strikingly beautiful to me, and then work with it as musical material. This piece juxtaposes a recording of wave action which I made down by a lake in Montana, with long creaking and singing tones generated by a metal dock responding to wave action at the Hoboken Ferry Terminal (New Jersey). The lake waves needed only a little editing but I wanted to bring out those singing tones in the dock and used filtering and convolution reverb to create something almost choral and the heart of the piece.

PT: Thank you for that, I expected/suspected something along those lines but it was nevertheless enlightening! I’m not sure how the next question follows that but somehow it arose just now: Do you regard your work as activism?

AL: No, I don’t regard my work as activism. (with the exception of In Our Name (2009-10), a setting of three poems written by three men while imprisoned in Guantánamo: Emad Abdullah Hassan, Osama Abu Kabir and Jumah Al-Dossari, and intended as a protest against their abuse and torture). Recently I have been reading Rebecca Solnit’s new book, Orwell’s Roses in which she quotes the artist Zoe Leonard as saying „You go through all of the fighting not because you want to fight, but because you want to get somewhere as a people. You want to help create a world where you can sit around and think about clouds. That should be our right as human beings.” And later, writing about Orwell’s Nineteen-Eighty-Four Solnit comments „Things that matter for their own sake and serve no larger purpose or practical agenda recur as ideals in the book. The thrush in the Golden Country sings for no perceptible purpose, and listening to it he falls out of fear and out of thought into pure being”. Yes, something which I think tends to happen rather easily when one can sit and listen to water.

PT: I don’t know this book but it’s funny you mentioned Solnit because time and again I keep coming back to Hope in the Dark. But no matter how many times I try to find this hope it’s getting harder. I’m often reminded about „in vain” by Georg Friedrich Haas on which he said something to the effect that it’s about all our efforts being in vain. Which is if course paradoxical, it being such a huge work and Haas continuing to compose after nevertheless.

What I’m probably trying to say is that recently I have a hard time finding sense not only in dealing with art or activism (or any activity for that matter). So, risking too naïve and/or personal question, I’d love to know what keeps you going?

AL: Yes, this is a dark time and mid-winter makes it even heavier I find. Truthfully, what keeps me going is the friendship of the friends whom I love and who have stayed in close touch with me these past two years so thoughtfully. And then, just when I think that my time of making new work is ending, a proposal for a new project comes along which looks challenging, often on the recommendation of a friend, and is something I can’t turn away, something surprising, so I take it on, and keep going. Years ago I consciously followed a policy of “say yes to everything”. I choose carefully these days, but the general impulse is a good one, I think.

(November 2021 – February 2022)